Back in the ’90s, when I was studying math at university, professors loved to joke about “an ideal spherical cow in a vacuum.”

They used this bizarre metaphor to describe a great theory that, unfortunately, only works under unrealistically perfect conditions. It was a bit like a plane that only flies in ideal weather.

I see large herds of well-fed spherical cows in business strategy books. Many of them argue that strategy means answering these four questions:

- Where are we now?

- Where do we want to be?

- How will we get there?

- What changes do we need to make it happen?

Roger Martin, a renowned strategist, offered another set of questions in his book with a bold subtitle, How Strategy Really Works (seriously??):

- What are our winning aspirations?

- Where will we play?

- How will we win in chosen markets?

- What capabilities must be in place to win?

- What management systems are required?

In a lab, it would look like a recipe for success. In the real world? Not so much.

Although these theories look perfectly logical, they have a flaw makштп them hard to apply.

Would you buy a car that only starts once every 200 tries?

In his book How Big Things Get Done, Bent Flyvbjerg shares some shocking numbers. His research team has built a database of over 16,000 projects from many countries. It includes both megaprojects, like building skyscrapers or digitizing government institutions, and smaller projects. The projects come from various domains – from the aerospace industry to home renovation.

And Flyvbjerg’s statistic is thought-provoking:

- Only 47,9% of projects hit the mark on cost

- Only 8.5 % of projects hit the mark on both cost and time

- And just 0.5% nail cost, time, and benefits

Basically, it means that only one out of 200 projects goes as planned. Only 80 projects out of 16,000 were completely successful.

Bent Flyvbjerg doesn’t share specific stats on business strategies. But, according to textbooks, any strategy is a project.

And it's safe to assume that 199 out of 200 strategies also fail. If somebody offered you a car that would start only once out of 200 tries, would you buy it? I don’t believe that 15,920 out of 16,000 projects had incompetent leaders. There must be another explanation.

Finite and Infinite Games

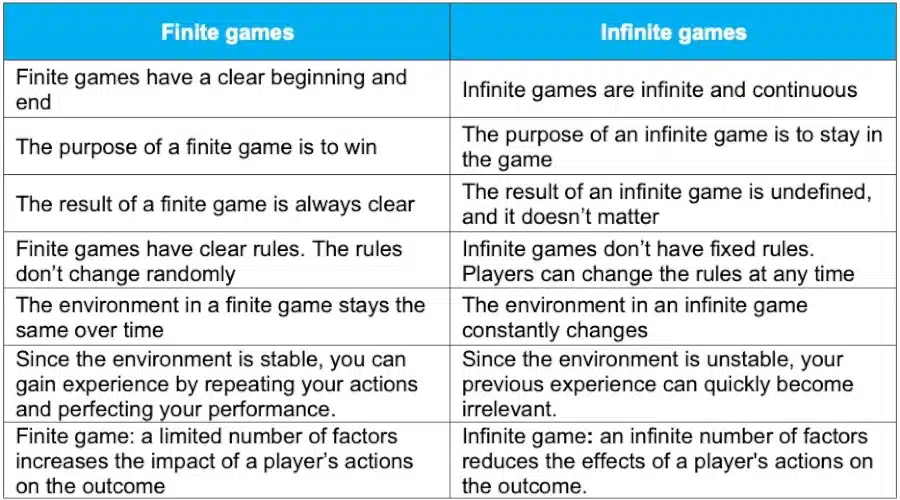

James P. Carse coined the term ‘finite and infinite games’ in his 1986 book Finite and Infinite Games: A Vision of Life as Play and Possibility.

Carse argued that people play two types of games throughout their lives – finite games and infinite games.

I’ve adjusted his definitions of the games, but I’ve kept the main idea intact:

Football, tennis, earning a degree, and a beauty pageant are finite games.

Business, marriage, politics, learning, and life itself are infinite games.

For instance:

- A football match has a clear beginning and end

- The purpose of a game is to defeat rivals

- The result of a game is always clear (one team wins, or it ends in a draw)

- Football has clear rules, and they don’t change arbitrarily

- Teams play football in stadiums, and all the stadiums are very similar.

- David Beckham and other great footballers honed their skills by practicing their shots for hours.

- In football, a limited number of factors, such as your rivals' strategies, can influence your victory.

What about business?

- Business can have a clear beginning (when someone establishes a company) but doesn’t have a clear end. The company stays in the game as long as it exists.

- The purpose of a business is to stay in the game – not to win. All victories in business are temporary, they mean little in the long run. Intel used to be a winner – how does it help the company today?

- The result of the game is unclear. Who’s won an e-commerce battle?

- There are no rules in business and strategy.

- Ask the companies caught off guard by Trump’s recent decisions about the stability of the business environment.

- Strategy is always about doing something no one else has ever done before.

In business, hundreds of factors can block your way to success.

The four questions from business textbooks and Roger Martin’s five questions work very well – but only in finite games.

Applying them to strategy is like swimming in a pool wearing full hockey gear.

Set a goal – plan – act – lose

Most strategists build their theories around a simple idea: you should set a goal and find a way there. Sounds great, but who on earth has ever proved that it works? Why has it become an axiom? Why do we apply it without question?

This approach looks ideal for small, short-term projects. However, if you look at Bent Flyvbjerg’s stats, even such projects often fail. But if you build a bridge, skyscraper, or tunnel, you're in a better position than a CEO crafting a strategy.

- You can research the site to make sure it’s suitable for building a stadium or bridge

- You’re most likely experienced in construction

- You’re working in relatively stable conditions

- The laws of building physics work the same way everywhere on the planet

A CEO faces other difficulties:

- What’s the goal? If you’re building a bridge, your goal is… the bridge. Roger Martin tells you to ‘win,’ but you can’t ‘win’ in business. You can win in a quarter or a year, but, as we know, short-term goals make us short-sighted.

- Any strategic goal is nothing but a fantasy, a dream because no one can truly prove its relevance and achievability. You’re not a taxi driver setting up directions to the airport. You’re more like Columbus, sailing off to find something that might not even be out there.

- There are no rules in business, no ‘laws of physics’ to rely on.

- The environment changes every second. Imagine setting off from Boston to New York, only to find out halfway that the highway now leads to Ottawa – and that New York doesn’t exist anymore.

- Your experience is more of a liability than an asset. Re-learning is always harder than learning.

- Thousands of factors affect your strategy, from the name of the guy in the Oval Office to your landlord raising the rent.

Thinking you can skewer this unstable, constantly shifting world onto the rigid spit of your plans is as naive as trying to guess where a fly will land in a minute. Even if we try to turn an infinite game into a finite one, it won't make it any less infinite. We need to embrace the rules and play by them.

What we can do

We have to admit – business is an infinite game. We should accept our inability to control most of the factors affecting our success. But that’s good news, not bad.

It will allow us to stop pretending we are all-powerful and focus on what we can change.

- We can’t set a strategic goal as a point in the future, but rather as a direction and the speed of our growth.

- We should rely on short-term planning as much as possible, but keep it aligned with our long-term direction.

- We should follow Jeff Bezos’s advice and divide all the decisions into reversible and irreversible. If a decision is reversible, we can improvise and experiment. When a decision is irreversible, risk management becomes essential.

Conclusion

In traditional strategic management, there’s this underlying idea that strategy is a one-time decision followed by action. But that only works in finite games. In infinite games, you do strategy every day — literally. We need to embrace the fact that long-term planning in such an ever-changing, fluid world is impossible.

Adaptivity is more important than the ability to plan.